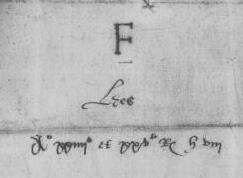

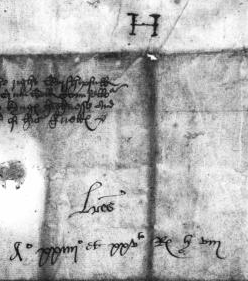

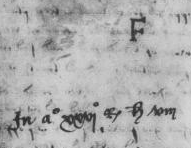

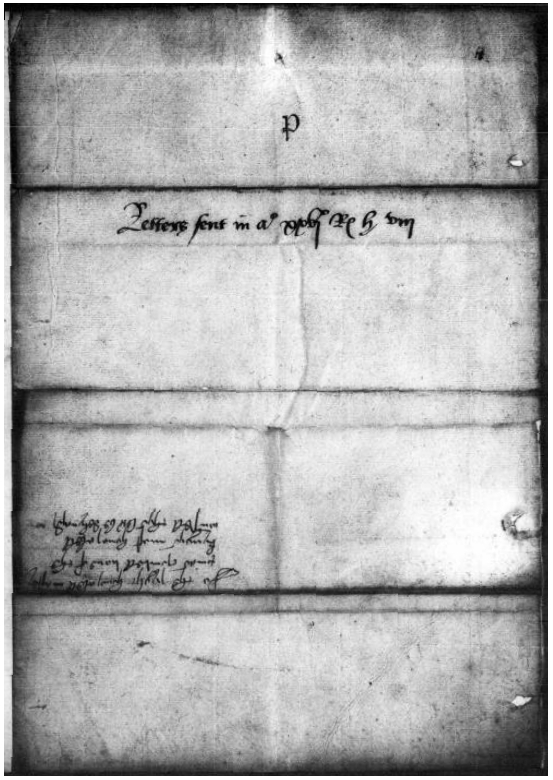

National Archives SP 60/2 f.48 (dorse detail)

1534 seems to be a transitional period for the manner in which Thomas Cromwell’s incoming correspondence was managed. Investigating starts at the back of these letters, the thicket of signs acquired over 500 years: folio numbering, dating, annotations of subjects, names and matters. At the bottom layer of this thicket is the letter-writer’s superscription, and then annotations of receipt, on what becomes a scribal work surface. A few unique filing annotations appear for a short period of time which seem to be linked to the record-keeping practice which I began to investigate in the previous post on cover sheets.

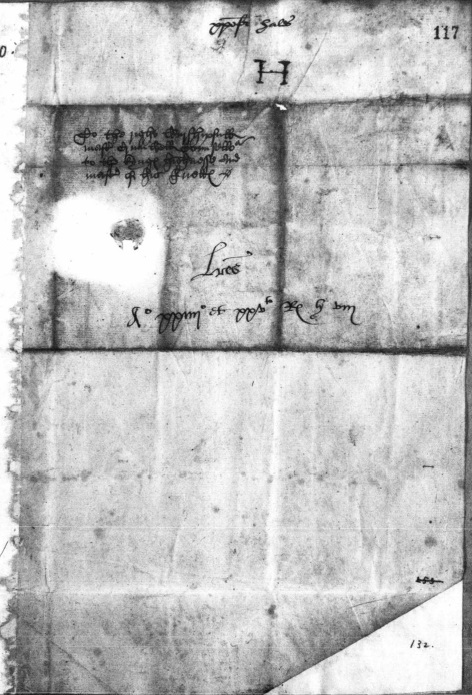

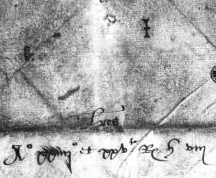

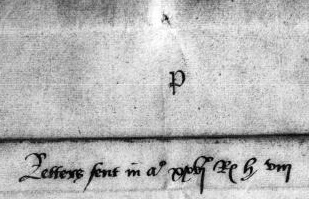

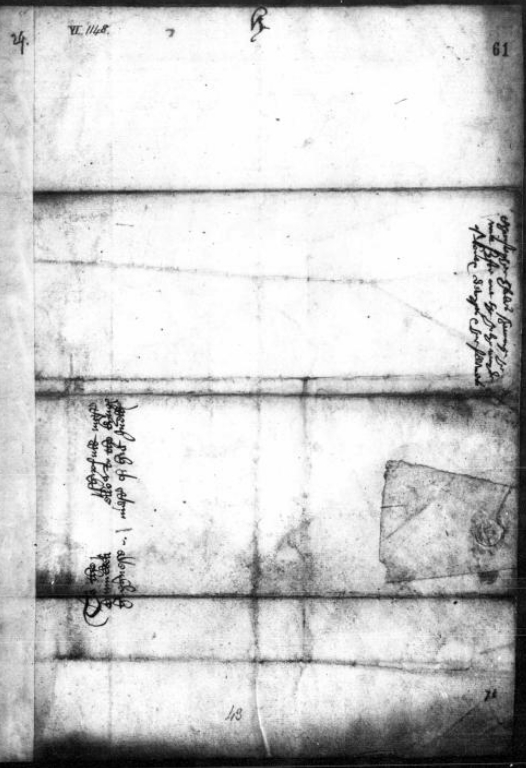

National Archives SP 60/2 f.50 (dorse detail)

Evidence for this practice barely makes an appearance at all in the State Papers, but the following focus on these types of annotation will show an indexical method at work. Most annotations on correspondence such as the fairly habitual recording of the name of the author do not have such a specific function. Along with the cover sheets of the previous post, these are contemporaneous and process-specific. I will start with some observations and introduce a hypothesis to account for their use. (1)

There are 3 types of evidence for some kind of systematic organization that appear on the dorse of correspondence in the 1533-1534 period: the cover sheets for the span of one or two regnal years already described,

“Letters sent in anno xxvi R H VIII”

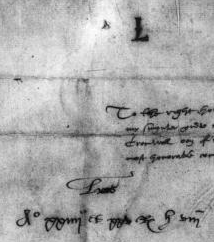

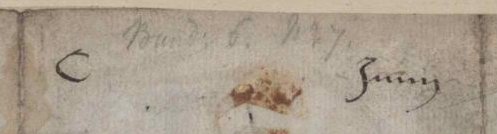

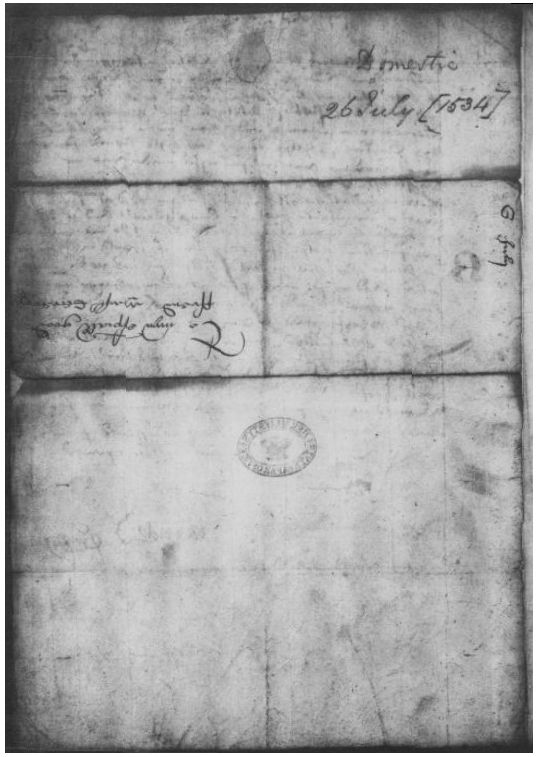

National Archives SP 1/79 f.78 (dorse)

a further 9 or 10 items on which only a letter of the alphabet is informally drawn,

National Archives SP 1/79 f.61 (dorse)

and approximately 20 on which there are a combination of letter and month along one edge.

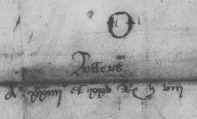

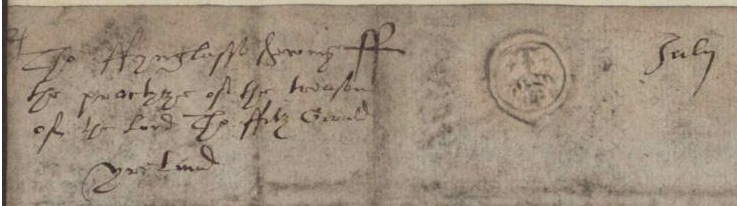

National Archives SP 1/85 f.72 (dorse)

The alphabetical characters on all 3 types index the name of the author of the correspondence on which they are placed. The letter and month combination index the author and month written.

First, considering this combination of letter and month, it is a remnant of an unknown but particular goal-directed activity. When combined with a year, the two abstracted elements provide a filing location, and an intellectual order, although the relationship is not given: months arranged by name or names arranged by month? Being such a rare and short-lived form of annotation we can assume it was not a regular office practice, but peculiar to one individual, who followed a habit, or invented it for the occasion.

National Archives SP 1/85 f.45 (detail from dorse)

The clerical occasion may have been sorting for future filing, returning an item to a place retrieved from, or some other interaction with the organization of correspondence. Whatever its necessity, it points to a certain structure, and what must have been a large volume of records, otherwise its use would not have been needed.

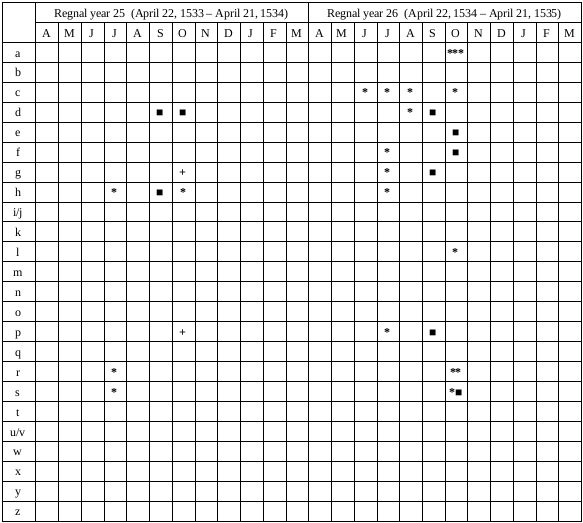

When considering that the 3 types could form inter-related elements of one system, their functions may become clearer. The following table illustrates the range by alphabet and the known or assumed dates given in the calendar entries for each piece of correspondence:

* = Month and letter annotations

■ = Single letter annotations

+ = 26th RY cover sheets (one is not dated so omitted here)

One can immediately observe that there are two groupings over time, from June/July to October, in both regnal years 25 and 26. A kind of mirroring can be observed in the continuity of surviving letter groups over the two years. It seems odd however that someone would be performing the same task in the same way for only these months over two years. The calendared dates may be wrong in some instances, but there are enough dates which are obviously correct to make this possibility irrelevant.

I think to make sense of this chronological range over two years we have to make an assumption: that in 1534 these items of 1533 correspondence (of any of the 3 types) were misfiled, and brought into the 26th regnal year aggregation. I will come to the reasoning for this shortly. If we accept this then all these annotations should be considered as made in 1534.

If the single regal year aggregation (year 26) is a development of the previous two-year aggregation then the next logical division would be monthly, in response to an increasing amount of correspondence to manage. This is what the letter/month annotations point to. For regnal year 26 I think incoming correspondence was on receipt collected in groups by the initial letter of the author’s name, and within those groups chronologically, but face down. This regular chronological accumulation may be a difference from the previous two regnal year aggregates. It is how most modern office files grow, forming themselves in reverse chronological order, with the most recent documents on top.

National Archives SP 1/85 f.106 (detail from dorse)

The 26th regnal year did not end in October, so why do the annotations end there? I can think of two possible reasons. September 29 is Michaelmas, a division frequently used at the time for accounting periods; in fact inventories of Cromwell’s papers made by his servants frequently make use of this as a division. Perhaps more significantly, in early October Cromwell obtained the office of Master of the Rolls, which did not replace his position as principal secretary, but augmented his power. It increased his staff and shifted his base of operations to include a new physical location on Chancery Lane. October 1534 then would have been a time of putting things in order by his staff in his previous ‘home office’.

It is this activity that can account for the creation of the letter and month annotations. They are pieces of correspondence which were found in out of the way places, or otherwise presented for filing within the already accumulated April to October stacks or files. Around the same time, in anticipation of closing these files, the top dorse was given a temporary letter label. This accounts for the pattern we see in the table above for the single-letter annotations on correspondence: they are written in September or October.

The last step in the process of creating these files was the more formal regnal year labeling, on the topmost dorse of the by-now bound file, of which there are 3 examples extant. Again we can look to their dating to confirm this. One was written on October 6, one was written in October 14th, and the third is unknown. This last step seems to confirm their chronological order, at least to the extant of collecting by month. The cover sheets of the previous years do not have this pattern.

So what we have, represented by these inconspicuous labels, is a sequence of interrelated activities: filing, labeling files, and then closing files with the addition of further identification of the series.

Following are the annotations and UK National Archives document references:

|

SP 1/86 f.34 |

A |

October |

|

SP 1/86 f.110 |

A |

October |

|

SP 1/86 f.127 |

A |

October |

|

SP 60/2 f.48 |

C |

June |

|

SP 1/85 f.45 |

C |

July |

|

SP 1/85 f.103 |

C |

August |

|

SP 1/86 f.50 |

C |

October |

|

SP 1/85 f.106 |

D |

August |

|

SP 1/85 f.144 |

D |

– |

|

SP 1/79 f.146 |

D |

– |

|

SP 1/79 f.96 |

D |

– |

|

SP 1/86 f.18 |

E? |

– |

|

SP 60/2 f.50 |

F |

July |

|

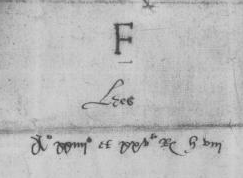

SP 1/86 f.14 |

F |

– |

|

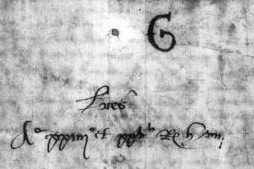

SP 1/85 f.72 |

G |

July |

|

SP 1/85 f.178 |

G? |

– |

|

SP 1/238 f.125 |

G? |

– |

|

SP 1/238 f.92 |

H |

July |

|

SP 1/85 f.47 |

H |

July |

|

SP 1/79 f.166 |

H |

October |

|

SP 1/79 f.61 |

H |

– |

|

SP 1/86 f.128 |

L |

October |

|

SP 1/85 f.62 |

P |

July |

|

SP 1/85 f.170 |

P |

– |

|

SP 1/77 f.185 |

R |

July |

|

SP 1/86 f.32 |

R |

October |

|

SP 1/86 f.106 |

R |

October |

|

SP 1/78 f.55 |

S |

July |

|

SP 1/86 f.23 |

S |

October |

|

SP 1/86 f.12 |

S |

– |

(1) This evidence is restricted to what I have observed on the surrogate images, not the original records in the National Archives. I take these marks to be contemporaneous with their absorption into Cromwell’s record-keeping systems because their handwriting seems consistent, as well as the fact a few of the months recorded are not included in the text of the correspondence, so must of been known by the scribe (i.e. SP 1/86 f.128). The logic of the reconstruction also speaks to their creation while the office was active.