“We have here greit nede of clerkes…”

William Brabazon in Ireland to Thomas Cromwell, via William Body, October 1536 (SP 60/3 203v)

This communication, from one servant of the king to another, carried by one in private service, reflects a larger mid-sixteenth century need for secretarial labour. Projecting sovereign power by the written word was not strictly a rhetorical phenomenon; it was dependent on the skills and techniques of administrative actors. In England at this time a diffuse “service aristocracy” of nobility and gentry carried out the executive actions of the crown, undercutting rival claims to sovereign authority. (Robertson 1990) The record-keeping practices of this context reflect a secretarial culture embedded in a chain of master-servant relations, and in the case of Thomas Cromwell, this de-centralized structure in tension with the effects of a consolidation of power by one official.

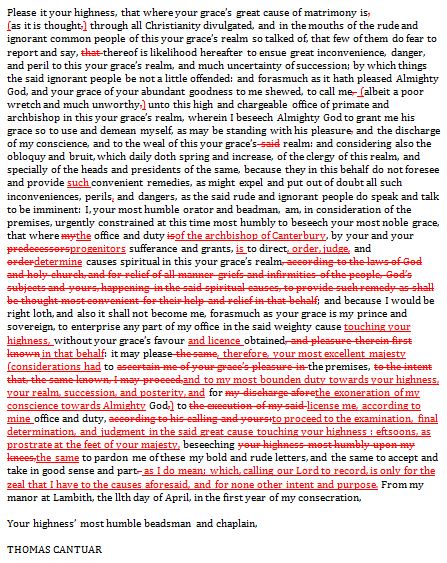

Attention to material differences among contemporaneous technologies provide a means to historicize them. Continuing my exploration of Thomas Cromwell’s secretarial practices, I will begin with one of the records management tools which were in use: lists of documents in the custody of Cromwell or his household staff. These were most often referred to as a catalogue, but this document type goes by various names which fall within the genre of inventory. My introduction to this topic is here. I will also compare this type of inventory with a model presented by historian Randolph Head.

The manner of physical and conceptual control exercised over records speaks to the character of integration those records had in a social system. The secretarial catalogue of early modern England functioned as an instrument of custodial relationship, a record of possession and acknowledgement of responsibility. In documentary form it followed the typical reporting device of an ordered list, used for collection of the particulars of property, summing up of debts and obligations, the seizure of papers, etc.

The catalogue examined here is in a bound volume held by the National Archives of the UK, which prior to 1846 had been in a central government Treasury location, known as the Chapter House. The individual records it contains got to the Treasury upon the arrest of Thomas Cromwell in 1540. The volume, probably created in the early 1800s, is one of five described as “Muniments and Memoranda of Thomas Cromwell.” This particular volume (E 36/143) contains inventories of writings and “remembrances” (to-do lists).

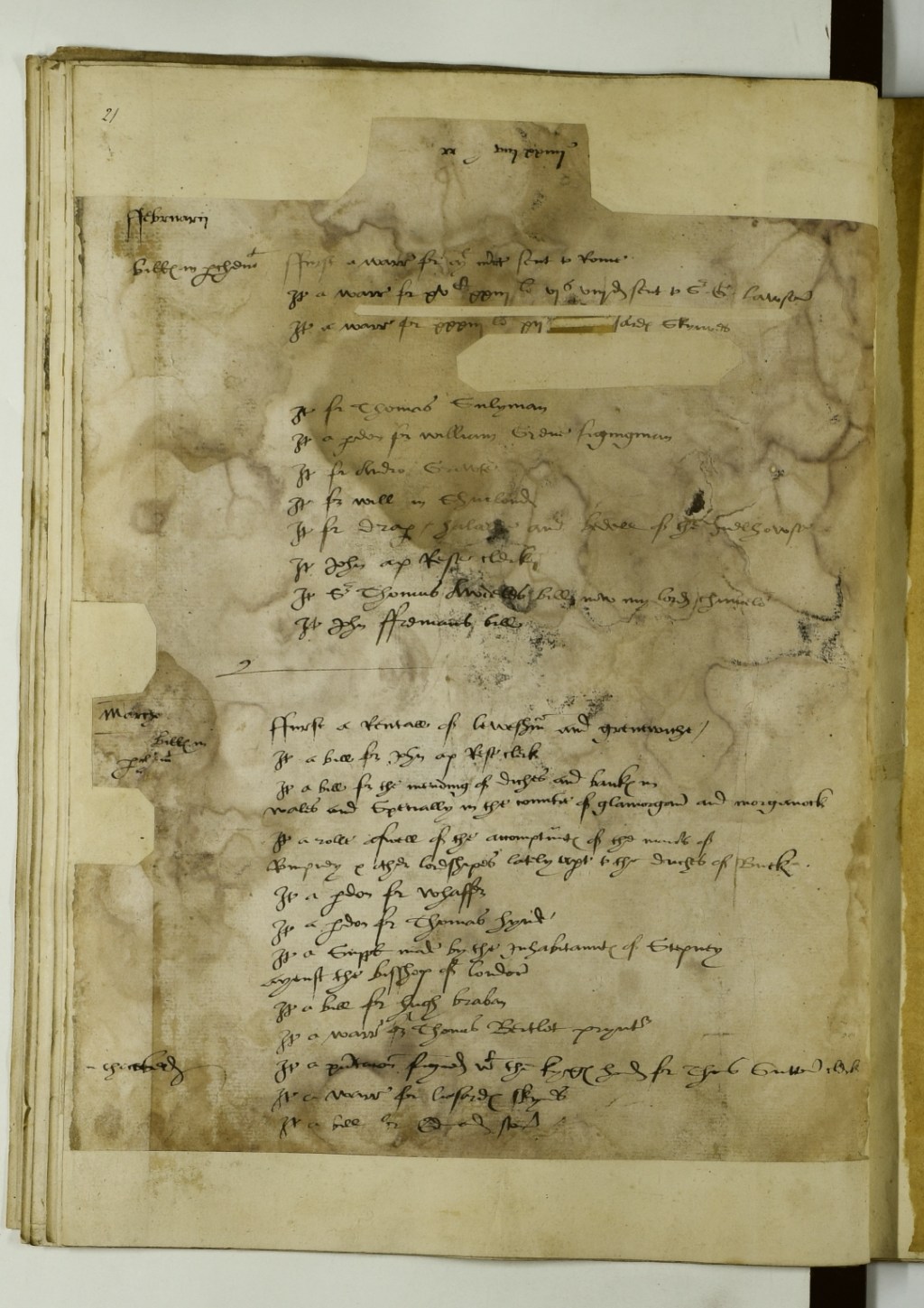

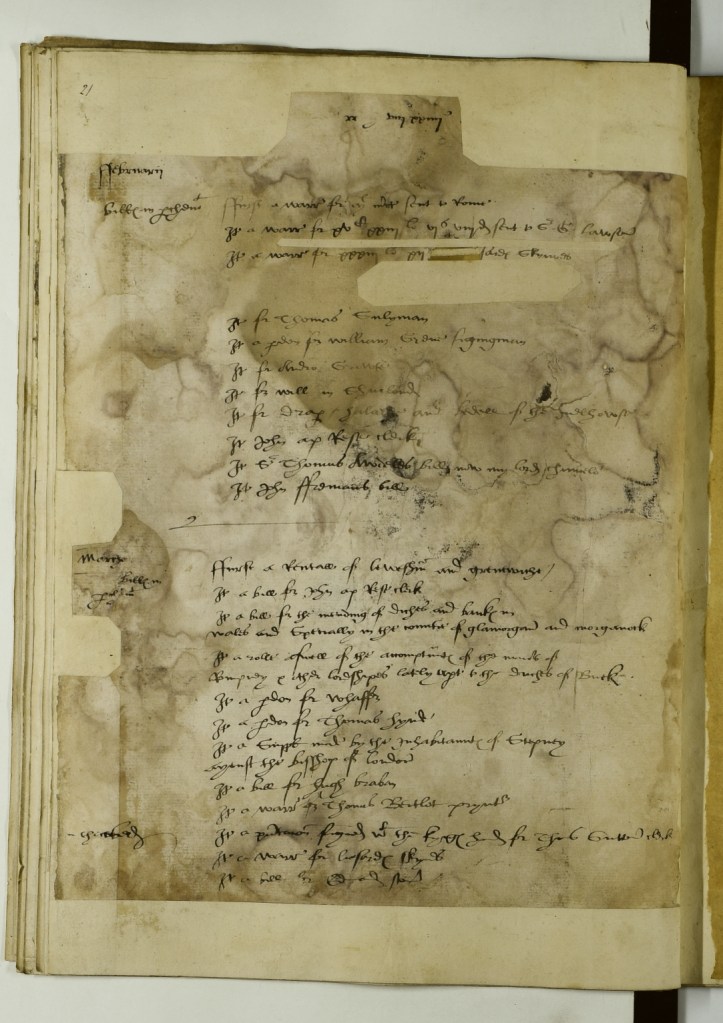

The particular list described below is one of about four separate lists brought together to form “A catalogue of my master’s writings, being in my master’s closet, that were brought since All Hallow tide, Anno 24 R. [H.] viij” (TNA E 36/143 f. 1-21). Translating from the conventions of the legal year, the catalogue includes documents received since November 1, 1532. Going by internal evidence, the date range extends to about March 1533. The items of the catalogue, represented by brief descriptions, include a variety of documents and bundles, but largely exclude correspondence. As in other catalogues made in this office environment, notwithstanding a few groupings by month or document type, each listed item is unrelated to its neighbors.

Within the separate lists which make up the catalogue various headers and marginal notes sometimes divide and describe groups of documents (“in parchment,” “March” etc.), something also evident in a few other catalogues. But subject matter groupings or descriptions are noticeably non-existent, a general characteristic of these inventories. The particular list I will describe here has features which set it apart from the usual type found among the surviving papers of this office.

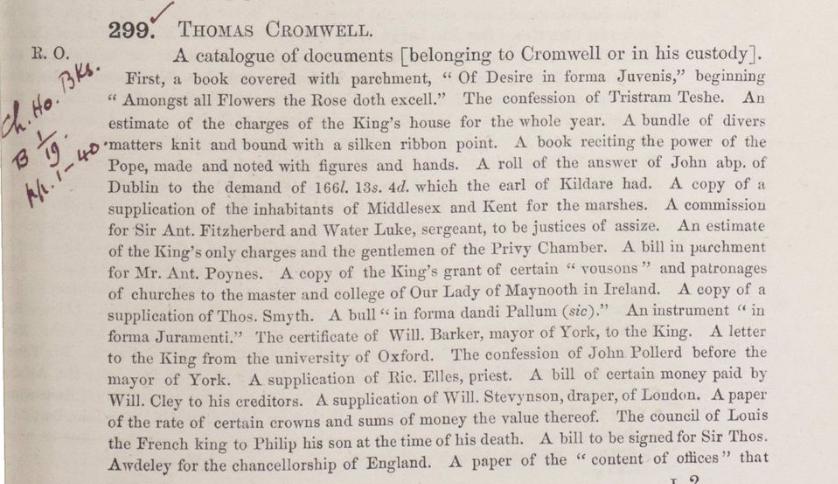

The extraordinary difference is the identification of specific locations where documents are located. This is unusual for catalogues in the Cromwell archive. Looking closely at the document now, one can see something like a finding aid taking shape; the systematization is tentative, as though it was thought out as the list was being created.

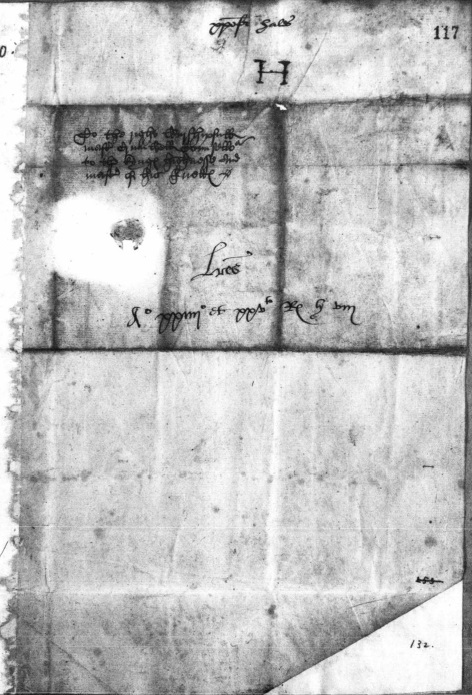

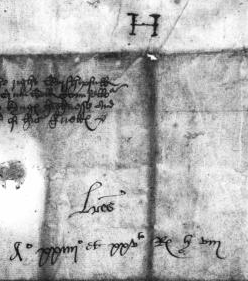

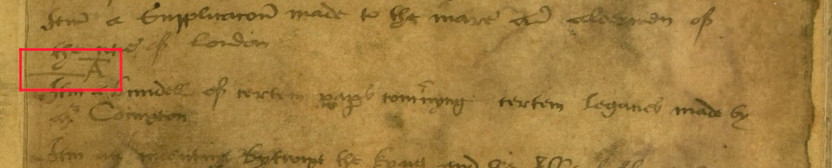

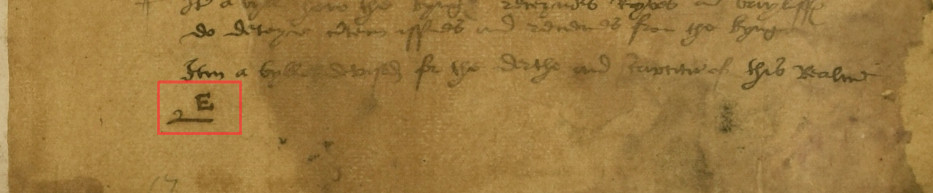

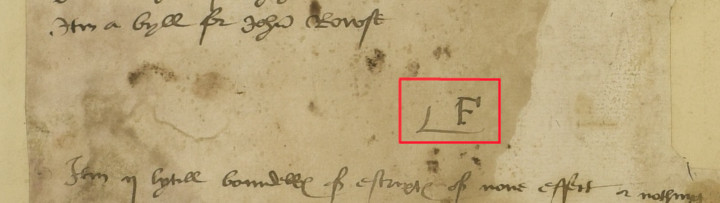

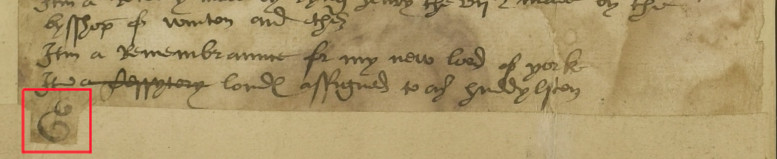

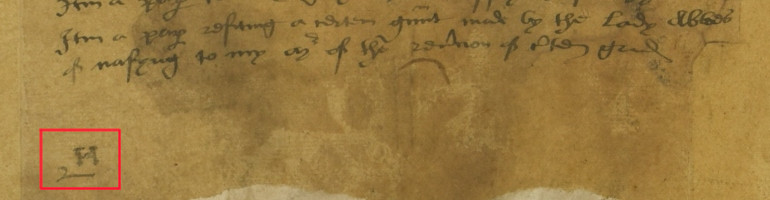

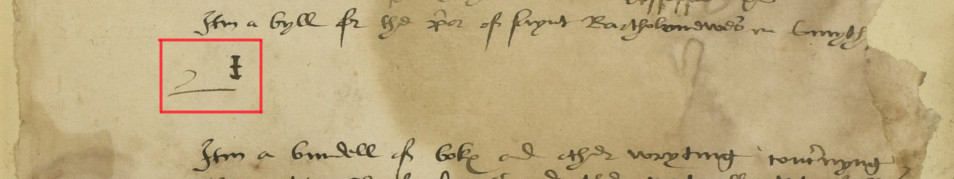

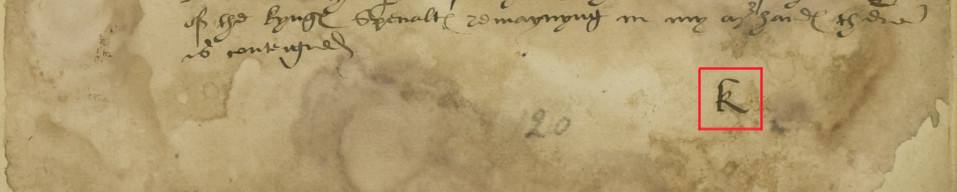

The drafter(s) were evidently working with piles of documents and fitting them in physical containers. This assumption is based on the list’s division by blank spaces between groups of items, and symbols which seem to correspond to physical division. The sections are labeled, using the letters A to K, which we can assume indicated a corresponding location (but, there is no evidence as to what the specific location was: drawer, box, bag?). The recording of locations looks like a team task, added as the listing process progressed. The involvement of multiple writers is indicated by the variations in lettering, an inconsistent ensemble of secretary hand and other forms. What we are seeing is an act of organization, the household clerks at unfamiliar work placing documents in these locations. It is not therefore what we would consider an archival inventory drawn up retrospectively.

Note: The folio on which I believe the list begins (pp. 39-40) is incorrectly bound at the end.

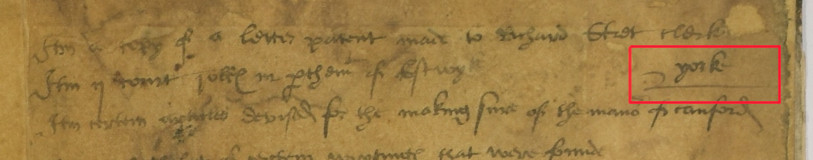

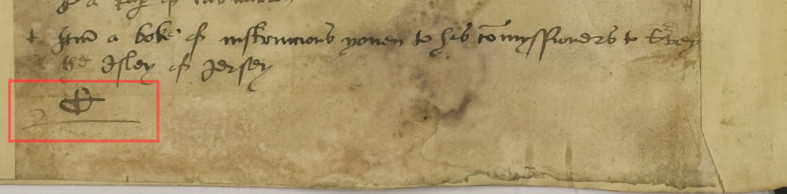

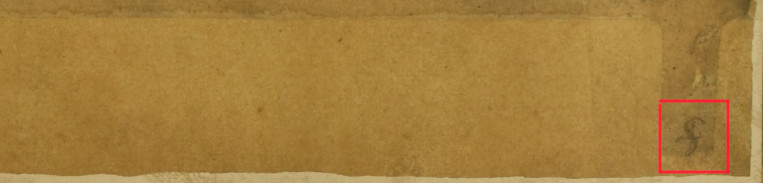

Within the increasingly confident system of letter identifiers there is one augmentation. If we accept the function of the symbol I’ve noted, a “York” section seems to be inserted within the “G” section, in a space on the right of the page:

I believe this refers to York House, a palace in London newly acquired by the King (to be renamed Whitehall), and a logical site for crown documents to be located. Perhaps one or more items on the list were moved there, and so annotated.

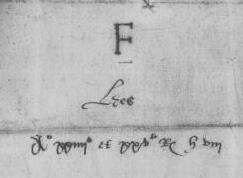

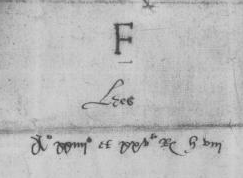

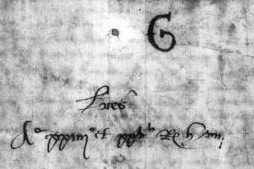

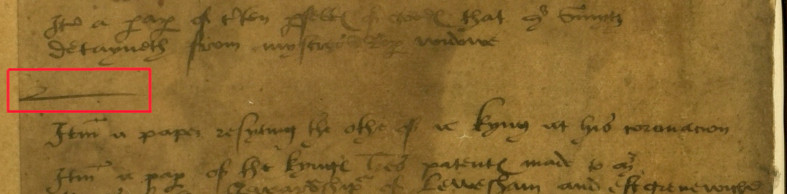

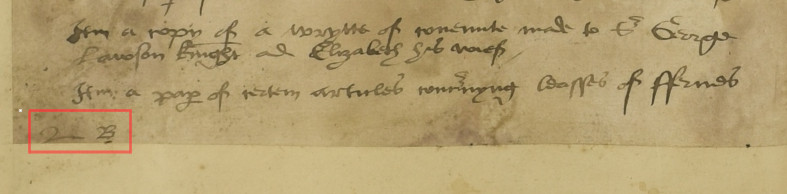

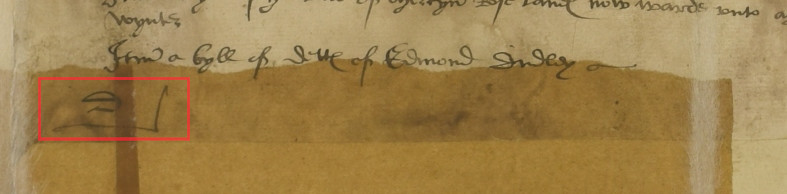

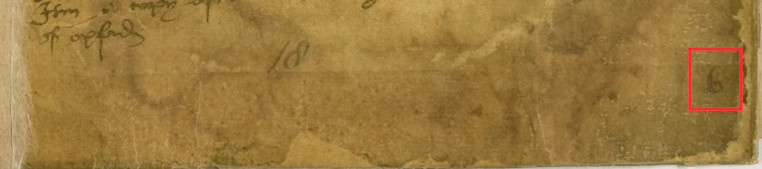

The architecture of the page is further utilized by the limited use of a special footer. The function of these footers is to indicate which lettered section is on the following page. It is an adaptive use of the catchword or stitchword, prevalent in both manuscript and printed book production, in which, below a page’s main text, the first word of the following page is duplicated. Although the standard explanation for this convention is its use in printed book collation, to guide the accuracy of page order, it was an ancient technique, and used in administrative writing well into the 20th century.

“K” could refer to a following section, but after the “I” section (we would not expect a “J” in this time period) there is only a single bundle described on this page, and only another single bundle on the verso. There the entire list ends, and without any further identifiers. Perhaps the letter K was added to indicate that the task would pick up at that location.

The first two catchwords, an italic “f” and a Roman capital “G”, do appear to be more clearly placed as catchwords, but the sections they refer to are on the verso of the same folio, so seem to be of little use in indicating the sequence of pages. However, it does make sense, if they were added much later in the history of this record, and if we add the generative element of decay.

The 16 pages of the list probably were originally 4 bifolia (4 sheets of paper each folded once), forming 8 leaves. The folded edges of the paper have deteriorated to the extent that the 8 leaves are separate, now reinforced and bound in a certain order (work probably carried out in the early 19th century). The order is not entirely correct. Folio 21 (pages 39 and 40) is the beginning of the list and should come before folio 14. This is based on the fact that these lists always display the same ordinal structure: Firstly a … / Also a … / Also a … etc. If this folio mix up occurred prior to binding then other accidental changes were possible, not just folio order, but also the order of folio sides (the order of pages if a leaf was flipped over). So the addition of these catchwords was probably made well after the list was first created, after the bifolia had deteriorated, during their archival life in the Treasury. A conclusion which points to the continuous use of the catalogue in this repository.

We can compare this catalogue with a model of the early modern archival inventory presented by historian Randolph Head. His study begins with a general definition of the inventory: “lists corresponding to accumulations of records.” (Head 1991, 140) Based on research conducted on select chancelleries of central Europe, Head describes a development of this document genre at the transition from medieval “treasury archive” to early modern “arsenal of authority.” The narrative of the European Archive, and terminology introduced by historian Robert-Henri Bautier, refer to the growing reliance governmental entities placed on the records at their disposal, and specifically those records securely stored and made accessible over time.

From that reliance emerged an archival finding aid. Head proposes that in response to the “intensification of governance” (Head 1991, 137) archivists in the repositories of public authority created new techniques of order and access. Building on the established codex forms of the chancellery (such as their tables of contents and indexes), and spatial logic (of vaults and other storage spaces), archivists created inventories to mirror organized and identifiable storage locations. Head’s definition of this new style inventory specifies its nature as a finding aid: a “record … created for the purpose of finding many other records by making their location possible to determine.” (Head 1991, 140)

Can we generalize from Head’s inventory model, or is the access and understanding of records by item listing described by Head peculiar to a certain conception of the archive? There is a family resemblance, but the catalogues of Cromwell’s office bring us out of the perspective of the European Archival paradigm, and into the practices of what we would now think of as current and semi-current records management. The codex and the treasury archive were not in this case a precursor set of techniques.

Head’s chancellery examples formed distinctive governmental structures, unlike the English Chancery, which had grown out of the royal household to form an institution with specific long-entrenched functions of sovereign authority, but was not the site of extensive governance which central European chancelleries had become. There, Head concludes, both the temporal and spacial overlap of one kind of institution, the “treasury archive,” with another, the “arsenal of authority,” saw a transfer of practical and discursive understanding of how to design archives; hence a type of inventory, a finding aid, developed.

The secretarial practices examined here had a weaker institutional setting than the chancelleries. Although the multifarious pursuance of the crown’s political goals was dependent on the methodical procedures of the Chancery and other offices of the crown, ordering the turbulent affairs of executive power by a single powerful official was reliant on processing authoritative commands and decisions by non-standardized means. The secretarial culture relied on habitual forms and techniques interrupted by splashes of unavoidable adaptation. The application of unformulated rules thus distinguishes the original 1533 catalogue from Head’s model finding aid.

Cromwell’s organizational ethic did not have the spatial and medial traditions of a chancellery to rely on, at least not directly. The documentary environment was determined by activities reflecting those mechanisms of a service aristocracy which executive power could harness or trigger. Cromwell’s household was not an office especially designed for long-term storage and access, as Head’s examples were. Like a chancellery however, the private spaces of crown servants were sites of political action and information control, hence the production, absorption, and storage of records. It is in this context that the surviving office catalogues should be seen.

Compared to the central European chancellery, time in the secretarial office was a scarce resource. The finding aid type of inventory described by Head was created over years and decades by dedicated archivists in stable institutional settings. The record-keeping concerns of Cromwell were largely restricted to immediate results. It was just this period of time, the early 1530s, that Cromwell took on an increasing load of official work, processed largely through his private space, by household servants, or servants and associates at a distance. There was not the time available to develop systematized finding aids. So, long-term preservation of, and access to, an ever increasing volume of records were issues which I would expect were abrupt and brief realizations. Hence the hurried adaptation of the standard custodial inventory form to record the specific locations of records. I like to think these broadly clerkish skills were analogous to the tinker’s ability to repair domestic receptacles with elements at hand.

The provenance of the 1533 catalogue includes its long life in a repository of the Treasury of the Exchequer. The evidence from this particular list shows that when placed in a new repository the catalogue could be shaped by re-activation. The scholarly persuasion of the Treasury archivists is well attested, so the practice of using catchwords would have been consistent with the archival culture Head describes. Consistent also, however, with a conventional secretarial skill of keeping papers in order. The catalogue’s new purpose is an open question: shorn of its custodial function, it became some sort of archival aid, not a formal finding aid, but an inventory with continual use as a source of information. In the early modern era different purposes, conditions, and temporalities of storage elicited different inventory forms.

Works Cited:

Head, Randolph. 2019. Making Archives in Early Modern Europe: Proof, Information, and Political Record-Keeping, 1400–1700. Cambridge University Press.

Robertson, Mary. 1990. Profit and purpose in the development of Thomas Cromwell’s landed estates. Journal of British Studies 29, No. 4 (Oct.): 317-346.